| Magazine section: Features |

The intoxication instinct

New Scientist vol 184 issue 2473 - 13 November 2004, page 32

From alcohol and cannabis to cocaine and LSD, it seems there are no limits to our appetite for mind-altering substances. What is it about human nature that drives us to get out of our heads, ask Helen Phillips and Graham Lawton

IN THE Smoke Shack, a "head shop" in Nelson, British Columbia, the air is thick with marijuana and the atmosphere is mellow as the staff stage a demo of their dope-related paraphernalia. The clients range from tourists and business types to the dreadlocked and dishevelled. All walks of life are welcome.

Over the border in the US, the police call to the man in the car for the last time. If he doesn't step out they will shoot. He stays put - maybe because he's embarrassed about being caught naked from the waist down, clearly aroused. Or maybe he's just too high on methamphetamine to care.

High up in the mountains of Peru the men brew coca leaves into a tea. While they don't approve of the habit of snorting the powdered extract, the tea gives them a mild buzz that helps fight the headaches and nausea of altitude sickness. Up here, cocaine is part of life.

Lounging in a restaurant, two old friends share a second bottle of wine, sinking lower in their seats as they enjoy the numbing haze and warmth it creates. Later they'll order brandy. The bartender pours himself a cup of coffee. It's going to be a long shift.

As diverse as these episodes are, there is a clear common thread running through them: the pursuit of intoxication. Since prehistoric times, humans have been seeking out and using intoxicating substances. Most people who have ever lived have experienced a chemically induced altered state of consciousness, and the same is true of people alive today. That's not to say that everybody is constantly fighting the urge to get high, nor that intoxication is somehow a normal state of consciousness. But how many of us can claim never to have experienced an altered state, whether it be a caffeine kick to help us get going in the morning, a relaxing beer after work, a few puffs on a joint at a party or the euphoric high of ecstasy?

In the present prohibitionist climate it is difficult to talk about the use of psychoactive, literally "mind-altering", substances without focusing on their harmful and habit-forming properties. And it's true that excessive use of consciousness-altering drugs, both legal and illegal, is bad for individuals and bad for society. People who seek intoxication are taking risks with their health and flirting with addiction. Drugs can lead to crime, violence, accidents, family disintegration and social decay.

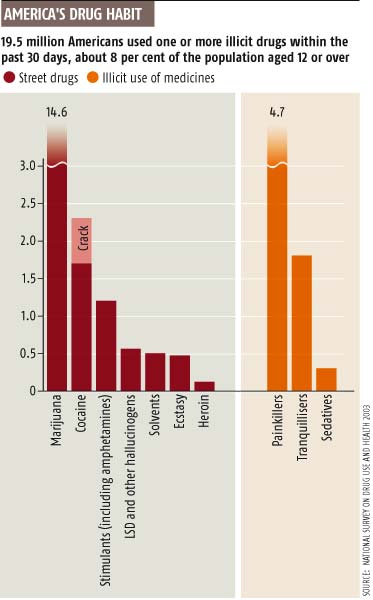

Nonetheless, intoxicants remain a part of most people's lives (see "Under the influence"). And indeed most of us are able to consume them in moderation without spiralling into abuse and addiction. Take alcohol, for example. Its potent psychoactive properties and potential for wreaking havoc are well known, yet the majority of people still drink and enjoy it without becoming alcoholics. There's also ample evidence that, despite public health campaigns and the threat of severe penalties, millions of people every year join the legions who have experimented with illegal substances, from cannabis and cocaine to ecstasy, amphetamines and LSD (for a guide to the most commonly used psychoactive drugs, see "A concise guide to mind - altering drugs").

It seems that intoxication in one form or another is universal, a part of who we are. "It's a natural part of consciousness to change one's consciousness," argues Rick Doblin, who runs the not-for-profit Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies in Sarasota, Florida. But why is it that we choose to alter our state of consciousness by dosing our brains with chemicals?

The answer is straightforward. We seek intoxication for a simple reason that we are almost too scared to admit - we like it. Intoxication can be fun, sociable, memorable, therapeutic, even mind-expanding. Saying as much in the present climate is not easy, but an increasing number of researchers now argue that unless we're prepared to look beyond the "drug problem" and acknowledge the positive aspects of intoxication, we are only seeing half the story - like researching sex while pretending it isn't fun.

A full understanding of intoxication, and the quest to achieve it, could have numerous pay-offs. For one thing there is the prospect of better ways to tackle abuse and addiction. There are also good reasons for studying intoxication as a phenomenon in its own right. What is it about psychoactive substances that we like? What do they tell us about who we are? Is there a way to get the good without the bad? Some researchers believe that such enquiries will lead to a new understanding of the human mind, including the mysteries of consciousness (see "A window on the mind"), or new treatments for mental illness. Others go as far as to argue that it is time for society to accept that intoxication is an inextricable part of human nature, and find a way to let us explore it openly.

The quest to understand intoxication wasn't always so constrained. Back in the 1950s, 60s and early 70s, many scientists took a very personal interest in it. In those more liberal days, researchers such as physician Andrew Weil, latterly of the National Institute for Mental Health in Maryland, and ethnobotanist Terrence McKenna charted the effects of many drugs, tested them in the lab and in the field, explored their mind-altering qualities first-hand, documented their use in different cultures, and suggested that many of the compounds had medicinal benefits.

Many of these pioneering researchers came to the conclusion that seeking intoxication was programmed into human nature. As Weil pointed out in his 1973 book The Natural Mind, from an early age children experiment with spinning around or hyperventilating to experience mind-altering giddiness. He suggested that when we get older, this quest to alter our feelings stays with us but we pursue it chemically as well as physically.

The spirit of personal research, however, was largely quashed in the late 70s and 80s as a US-led "war on drugs" took hold. Drug research became dominated by the "addiction paradigm", with pleasure and benefits strictly off-limits. "It was so controversial it had to be shut down altogether," says Charles Grob, director of the child and adolescent psychiatry department at Harbor-UCLA Medical Center in Torrance, California, whose interests lie with the potential medical use of psychedelics.

But some researchers carried on regardless. Ronald Siegel, now a psychopharmacologist at the University of California, Los Angeles, was one of them. As a psychology graduate student in the 60s he busied himself with studying pigeon memory. One day, a fellow student was arrested for marijuana possession, and his lawyer asked Siegel what he knew about the drug's effects. Not much, as it happened, so he brewed up an extract and watched what happened when a pigeon got stoned.

Ever since, he has been fascinated by intoxication, what it is and why we and other animals seek it. He managed to keep studying "controlled substances" such as LSD, mescaline, PCP, cocaine and psilocybin in his clinic, in animals and in volunteers, all legal and above board. He's passed out, thrown up, been attacked by intoxicated animals, and even been shot at by drugs barons - all in the name of research. And he has gained a unique perspective, spelled out in his 1989 book Intoxication: Life in pursuit of artificial paradise, which is being reissued next April by Park Street Press of Rochester, Vermont.

Siegel believes there is a strong biological drive to seek intoxication. "It's the fourth drive," he says. "After hunger, thirst and sex, there is intoxication." Whether we are seeking pleasure, stimulation, pain relief or escape, at the root of this drive, he says, is the motivation to feel "different from normal" - what has sometimes been called "a holiday from reality". Some people reach this state through travel, books, art, roller coasters, sport, religion, exploration, love, social contact or power. Others use intoxicants. "It's the same motivation," says Siegel. "We wouldn't live if we didn't seek to feel different."

One of the main "different" feelings we want to experience is pleasure. Pleasure, neuroscientists believe, is the brain's way of telling us that we are doing something that is good for survival, such as eating and sex. The circuits that create the feeling are driven by natural opioids and cannabinoids. No surprise, then, that we have a penchant for putting versions of these chemicals into our brains.

But the equation is not quite as simple as chemical in, pleasure out. At last month's Society for Neuroscience meeting in San Diego, California, neuroscientist Kent Berridge of the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor described preliminary work showing that rats given a natural cannabinoid, anandamide, seemed to become unusually partial to sweet tastes. Rats primed with anandamide had higher pleasure responses to sugar than unprimed rats. It seems that the cannabinoid may not just be pleasurable in its own right, but also enhances other pleasurable experiences, making the world seem a generally more likeable place. Perhaps this is one aspect of the well-known "munchies" effect of marijuana, they conclude.

A related idea is that some people take psychoactive substances to suppress "negative pleasure". George Koob, a neuroscientist and addiction specialist at the Scripps Research Institute in La Jolla, California, has proposed that the brain has a natural system for limiting the amount of pleasure we can feel. He argues that pleasure has to be transient or humans and other animals would get so absorbed in it that they would succumb to the next predator that came along. Koob thinks that the brain has a way of bringing us down - a kind of "anti-pleasure" mechanism if you like. What if this system goes into overdrive? "Some people seek excessive pleasure because they are born with too much anti-pleasure," he says. "They may take drugs to feel normal."

But there is more to intoxication than simply massaging our pleasure circuits. Some altered states, Siegel believes, have a utilitarian value. Just as many animals naturally seek medicinal plants such as antibiotics or emetics, we seek to medicate our minds. When we are agitated or in pain, emotionally as well as physically, we seek substances that tranquillise and sedate. When tired or depressed, we seek stimulants. According to some researchers, including Grob, this medicinal use is an underlying thread running through all forms of intoxication.

The drive to medicate mood is pervasive throughout the animal kingdom, Siegel says, and he and his colleagues have documented thousands of examples. Elephants, for instance, enjoy the taste of fermented fruit. They will usually just browse it, but if they lose their mate (elephants usually mate for life) they may seek oblivion in an alcoholic fruit binge, even drinking neat ethanol if researchers provide it. It's hard not to conclude that, like humans, they are drowning their sorrows. Stress can also lead animals to take intoxicants as a form of escape. When stressed by overcrowding, elephants are more motivated to seek alcohol. And fear can take its toll too. During the Vietnam war, Siegel and his team filmed water buffalo grazing on opium poppies to the point of addiction. And animals don't just take downers: there are numerous reports of goats guzzling stimulants such as coffee beans and the herbal amphetamine khat.

Medication with uppers and downers may be fairly easy to understand, but there are other intoxicants whose attractions are harder to fathom. These are the hallucinogens, which can't easily be explained in purely survivalist terms. Most animals actively avoid this category of intoxicant.

Despite this, some researchers believe that psychedelics can have a medicinal effect in humans. Doblin, for example, argues that the drastically altered states they induce can play a role in maintaining mental health. Hallucinogens - and to some extent cannabis and MDMA - allow us to escape, temporarily, from a reality ruled by logic, ego and time, and explore other aspects of our consciousness. "The brain functions best when it has access to altered states," he says.

This might sound like hippy mumbo-jumbo, but there is plenty of evidence in the medical literature that hallucinogens are effective against mental illness, including anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder, alcoholism and heroin addiction. Most of this research was done in the 1950s, but the field is now showing signs of a revival. Grob recently received approval to test psilocybin as a treatment for severe anxiety in terminally ill cancer patients, and there are ongoing studies in the use of psilocybin for otherwise untreatable cases of obsessive compulsive disorder, and MDMA for serious post-traumatic stress disorder.

Medicinal properties notwithstanding, there are other ideas to explain why people take psychedelics. Siegel found that he could persuade monkeys to voluntarily smoke the hallucinogen DMT (see "A concise guide to mind - altering drugs") when they were in a situation of severe sensory deprivation. He had already trained three rhesus monkeys to smoke for a reward, to study the effects of nicotine. When he laced their smoking tubes with DMT, they briefly tried it, then avoided it. But after several days in darkness, with no stimulation, the monkeys began to smoke DMT voluntarily. They ended up grasping at and chasing non-existent objects and hiding from invisible dangers. "This was the first demonstration of a non-human primate voluntarily taking a hallucinogenic drug," Siegel says. "We share the same motivation to light up our lives with chemical glimpses of another world." Boredom it seems, will drive animals to experiment, even when the experience is not altogether pleasurable.

The same drive to seek novelty or stave off boredom could explain why people take drugs that have overwhelmingly negative effects. PCP, for example, which some consider to be the most dangerous illegal drug, is a "dissociative" (see "A concise guide to mind - altering drugs"). Among its myriad effects are numbness, loss of coordination, paranoia, hallucinations, acute anxiety, mood swings and psychosis. But for some people the altered state is clearly worth it - PCP was hugely popular in the US in the 1970s. "People seem to say they liked feeling different or funny," says Siegel. "When there's nothing else to do, people will take anything to feel different."

In some ways novelty-seeking is a basic behavioural drive. Literature on child development reveals that once infants are no longer sleepy, hungry or thirsty, they will explore and seek new experiences. They wriggle their limbs, put things in their mouths, touch things, taste things and bash things together. Without this drive, they wouldn't learn anything about the world around them. Perhaps this spirit of exploration simply continues into adulthood in a different form.

There's another drive, too, that probably plays a role: risk-taking. For some people taking risks is itself pleasurable. According to Koob this might come from a slightly different brain system to the pleasure circuits. For animals that forage, there is always the risk of being attacked by a predator. In other words there is a conflict between seeking new foraging sites, or novelty, and risk. Evolution has got around this conundrum by making novelty rewarding and pleasurable in its own right.

Pleasure, excitement, therapy, novelty: seen in this light, the pursuit of intoxication looks very different from its standard portrayal as a pathological drive that must be suppressed before it leads to harm, addiction and squalor. Yet the mainstream debate on drugs, alcohol and tobacco seems unable to acknowledge that there is anything positive at all to say about intoxication. Instead it is locked into a sterile argument between prohibitionists and those who want to reduce the harmful effects by, for example, making heroin available on prescription. Both groups start from the belief that psychoactive substances are inherently harmful but disagree on what to do about it.

Some activists, however, are starting to argue for an entirely different attitude to intoxication. One prominent critic of the debate is Richard Glen Boire, director of the Center for Cognitive Liberty and Ethics in Davis, California. He believes that intoxication is not just a part of human nature, it is a basic human right. "Why should it be illegal to alter your style of thinking?" he says. "As long as you don't do any harm to anyone else, what you do in your own mind is as private as what you do in your own bedroom." Boire advocates changes to the law that would allow people to experiment with psychoactive substances at home or in designated public places. "It's the right of people to explore the full range of consciousness, and our duty as a society to accommodate that," he says.

Some scientists are moving in the same direction, arguing that instead of suppressing, medicalising and criminalising our basic drive to experience altered states we should apply ourselves to making it safer, healthier and less squalid - in short, to taking the "toxic" out of intoxication.

The approach favoured by Siegel is to tweak existing drugs to make them better, with shorter effects and no addictive potential. "What it would be like," he says, "if we had a drug like alcohol, which didn't lead to violence, fetal damage, liver failure, that was safe, wouldn't lead to drink driving and never gave you a hangover. What would be wrong with it medically? Maybe we'd even prescribe this alcohol substitute to help people relax." We could even design entirely new chemicals that allow us to experience all the pleasures, thrills and adventures of intoxication without the downsides. "This is not science fiction," says Siegel. "Civilisation will eventually take this direction."

Perhaps this would be the greatest contribution a full understanding of the intoxication instinct could offer - a spur for society to move beyond the irrational position of sanctioning caffeine, alcohol and tobacco while fighting a "war" against other psychoactive substances. David Lenson, a social theorist at the University of Massachusetts in Amhurst and author of the 1995 book On Drugs, makes this point by comparing the war on drugs with efforts to eradicate homosexuality: both are based on an incomplete understanding of human nature. Siegel, too, sees an analogy with sex. "We can't be expected to solve the AIDS problem by outlawing sex," he says. "We have to make drugs safe and healthy, because people are not going to be able to say no."

|

|

Helen Phillips

Graham Lawton